Mausoleum on Janiculum Hill (Mausoleo Ossario Garibaldino) – the struggle for national heritage

Mausoleo Ossario Garibaldino

Mausoleum on Janiculum Hill (Mausoleo Ossario Garibaldino), Giovanni Jacobucci

Mausoleo Ossario Garibaldino

Mausoleo Ossario Garibaldino, Giovanni Jacobucci

Mausoleo Ossario Garibaldino, Giovanni Jacobucci

Mausoleo Ossario Garibaldino, altar made out of red granite

Mausoleo Ossario Garibaldino

Alabaster column in the basement of the mausoleum, pic. Wikipedia

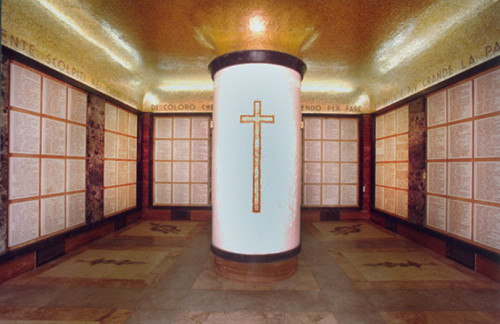

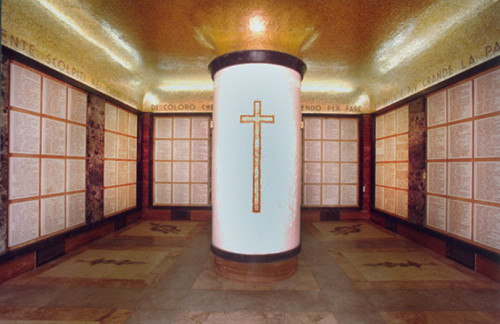

Mausoleo Ossario Garibaldino, plaques with the names of the fallen, the underground of the mausoleum, pic. Wikipedia

On Janiculum (Ganicolo) Hill, not far from the monumental dell’ Acqua Paola fountain (via Garibaldi), there is a structure made of travertine. And although its raw, compact forms betray the fact that it was built in Fascist times, it is dedicated to the memory of heroes who fought for freedom many decades earlier. Some of them became famous for defending the short-lived Roman Republic in 1849 against the Franco-Spanish regiments faithful to the pope, others died in 1870 in the struggle against papal forces defending the State of the Church.

On Janiculum (Ganicolo) Hill, not far from the monumental dell’ Acqua Paola fountain (via Garibaldi), there is a structure made of travertine. And although its raw, compact forms betray the fact that it was built in Fascist times, it is dedicated to the memory of heroes who fought for freedom many decades earlier. Some of them became famous for defending the short-lived Roman Republic in 1849 against the Franco-Spanish regiments faithful to the pope, others died in 1870 in the struggle against papal forces defending the State of the Church.

The year 1941, despite the success propaganda of the Mussolini regime, was difficult for Italy. The unsuccessful invasion of Greece and the struggle in the Balkans led to the death of fourteen thousand Italians (115 thousand wounded, 25 thousand missing in action). Things were no different in North Africa, where the casualties turned out to be much higher than expected. On the other hand, on the Eastern front, where Italian soldiers along with the Germans besieged Moscow, the catastrophe was only looming on the horizon. The film chronicles filled with propaganda, showing the activities of the Italian soldiers on various fronts depicted their devotion and courage. The dead, crippled, and suffering soldiers could not be shown. The numbers of casualties could not be given and neither could obituaries for them be published in the papers. Those who survived (without legs in wheelchairs) were shown in tears of joy as they were given medals of honor with crowds of people cheering for the Duce. The mothers and widows of the deceased were also shown as they were compassionately hugged by the leader of the nation. The propaganda constantly underlined the patriotism of the fighting soldiers and the devotion of the women working for the needs of the army. They were all united in struggle and heroism.

In such an atmosphere, with the participation of Mussolini, the mausoleum on Janiculum Hill was unveiled on 3 November 1941. It had awaited completion for good several decades since the idea to commemorate the heroes in the struggle for the unification of Italy had come about in 1878, while its initiators were the hero of those times and participant in the struggle of 1849 – Giuseppe Garibaldi and his son Menotti who started the process of the long-lasting search for the remains of the dead and establishing their identity. The idea came back to the forefront in the thirties of the XX century, while the man behind it was Garibaldi’s grandson – Ezio. It was at that time that the Society of Veterans (Società Reduci della Patrie Battaglie), an organization with Ezio at its helm, collected the appropriate funds, while Mussolini’s government approved the construction of the monument in a place known as Colle del Pino where on 30 June 1849, the final battle which ended in the defeat of the forces defending the Roman Republic, took place.

Risorgimento, meaning the long process of the unification of Italy, was willingly recalled by the Fascists. This movement fit perfectly into the nationalist ideology of the regime wanting to incite the inhabitants of Italy to build the power of a nation in opposition to all kinds of liberal, democratic, and socialist tendencies. Fascism was to unify and activate “the vital forces” of a nation, but also to recall the heroes of bygone times. In this way history became part of politics, becoming one of its driving forces.

The design of the mausoleum was the work of Giovanni Jacobucci. Monumental stairs lead to the raw portico on the plan of a square (quadrioportico) whose walls are filled with high arcades. Its central part houses an altar made out of red granite, decorated with engraved symbols of courage and fame taken from ancient art. Here we have the image of the she-wolf (the symbol of Rome), the inscription SPQR (Senatus, Populus Que Romanus), meaning “The Senate, and the People of Rome”), as well as swords, wreaths, shields, and eagles. The attica is adorned with inscriptions praising those who fall defending Rome as well as the slogan made famous by Garibaldi “Roma o morte” (Rome or death). On the cuboid pedestals, surrounding the plinth of the altar, with candles made out of bronze (lit during festivities), we can see the names of towns, where battles occurred.

In the rear of the structure, there are stairs leading down to the crypt. Passing through a bronze door, we find ourselves in the heart of the mausoleum, whose main part is occupied by a square chamber, with a monumental, alabaster column supporting it. The walls of the room are filled by thirty-six niches closed off with slabs, covered with inscriptions commemorating the names of one thousand six hundred fallen heroes, while the ceiling is covered with a gold mosaic. The porphyry sarcophagus located near the wall holds the remains of Goffredo Mameli – a hero of the Roman Republic, a poet and the companion of Garibaldi, but above all the creator of the Italian national anthem, who died at the young age of 22.

Today the mausoleum is a place of commemoration of the struggle for the unification of Italy, but also a recollection of the fall of the State of the Church. Its fall was caused by the assault of the armies of the king of Italy Victor Emmanuel II in August of 1870, while the then pope Pius IX in a gesture of protest proclaimed himself to be a prisoner of the Vatican. In 1871, Rome became the capital of the unified Kingdom of Italy. After signing the Lateran Pacts in 1929 with Mussolini, the subsequent pope, Pius XI “left prison” creating a new State of the Church and calling Mussolini “the providential father of Italy”.